Author Alexandre Delpy

Cahiers des Arts et Techniques d’Afrique du Nord, 1955

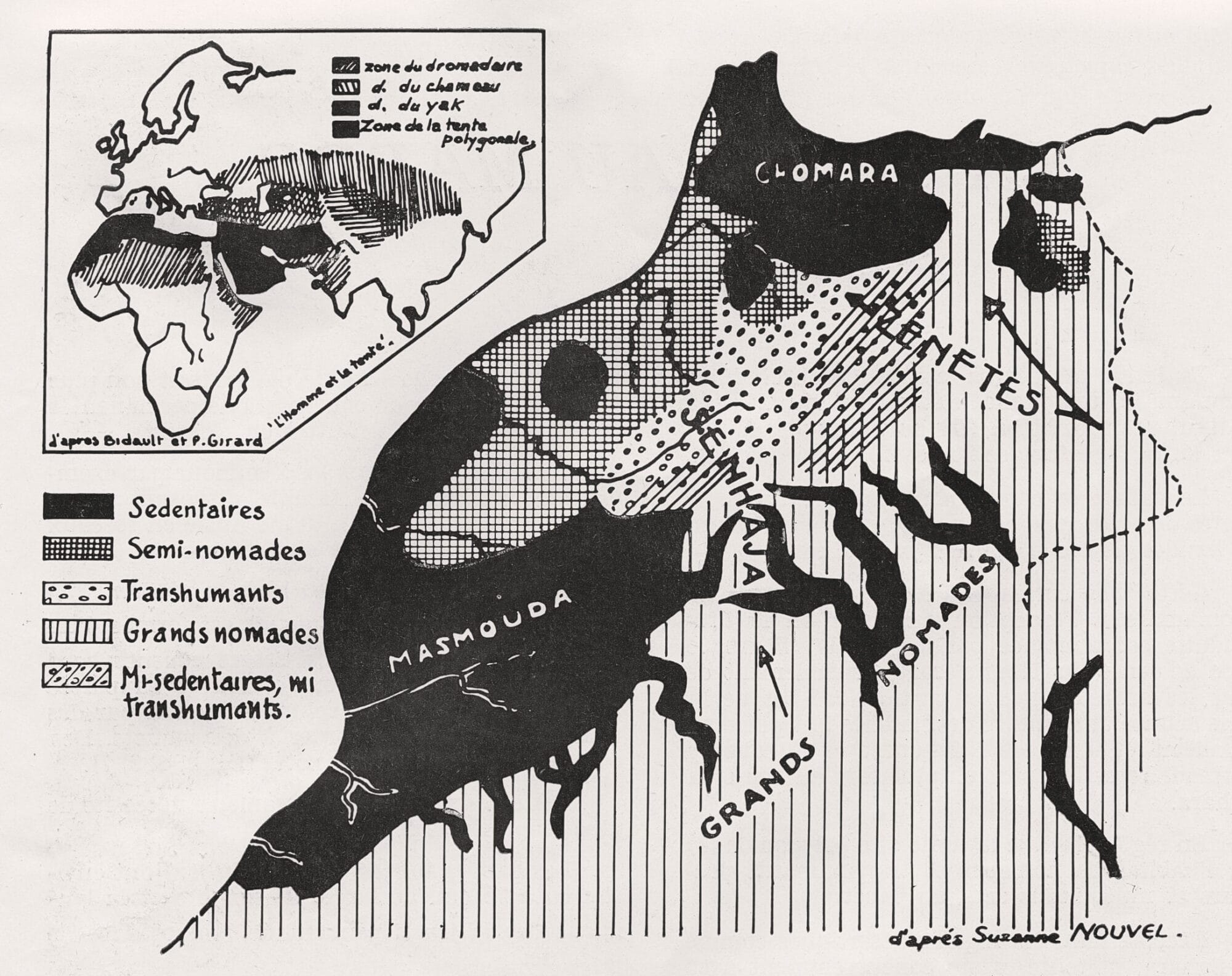

The Moroccan tent is part of a traditional type of dwelling that stretches across a vast region, from Tibet to the Atlantic, between longitudes 20° and 60° and latitudes 20° and 40° North (fig. 1).

The common feature of the different tents in this region is a roof made of sewn-together fabric strips, creating a flexible yet sturdy structure. This geographical area is generally associated with camel herding, except in Tibet, where the yak replaces the camel. Tibetan tents differ from others, as do those in the northeastern region, where camels gradually replace dromedaries. North of the Sahara, dromedaries become increasingly rare.

In general, “polygonal” tents (1) serve as dwellings for nomadic and transhumant Muslim herders, except in Tibet. Outside desert areas like the Sahara, tents coexist with permanent dwellings.

The Moroccan tent is closely related to those in other North African countries, particularly Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, all of which are descended from the Arab tent.

Historically, it was introduced to Morocco by invaders from the east, primarily the Senhaja, Zenata, and Hilalian Arab tribes (2). These waves of invasion, spread over five to six centuries, brought tents to all of northern Africa.

The vocabulary associated with tents in Morocco is predominantly of Arab origin, although pre-Islamic Berbers likely used tents similar to the Tuareg tents. However, the type of tent used today across North Africa and Mauritania surely derives from a prototype originating in Arabia.

According to the writings of Leo Africanus in the 16th century (3), the tent zone expanded and reached its peak in the early 20th century, covering regions like Loukkos to the north and the lower Moulouya to the east. Since then, colonization and the development of agriculture have reduced the area where tents are used, as nomadism declined.

Today, tents can still be found in certain regions, though often alongside permanent structures or reed huts. In regions like Zemmour, it is common to see the same family owning a solid house, a reed hut, and a tent.

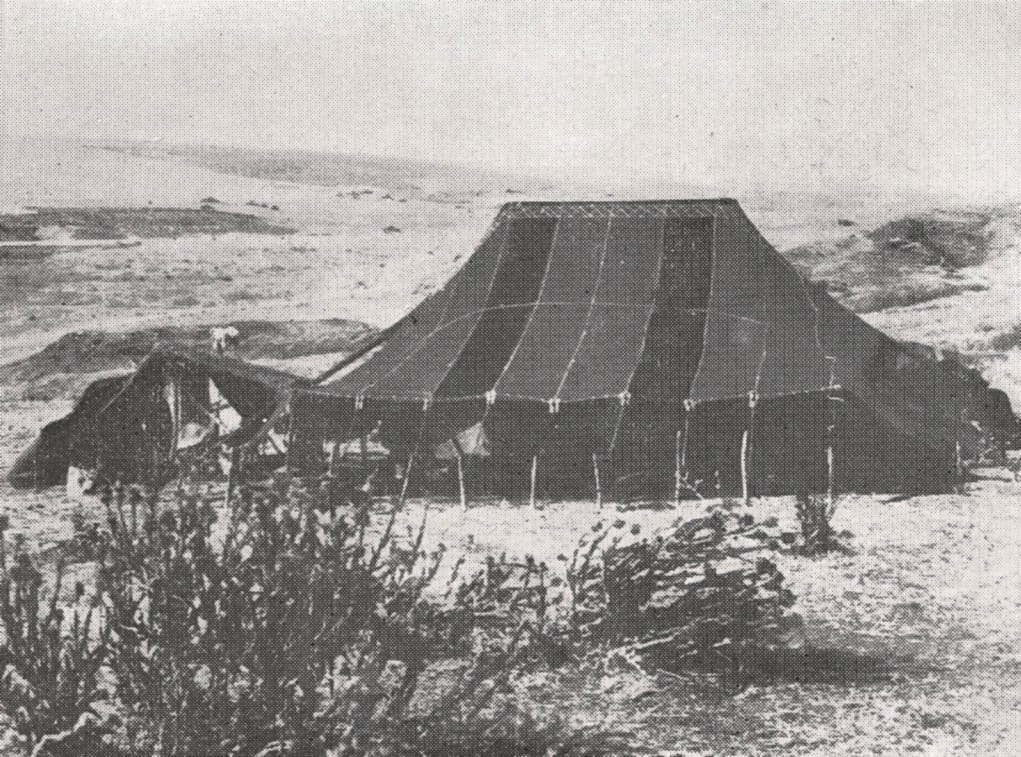

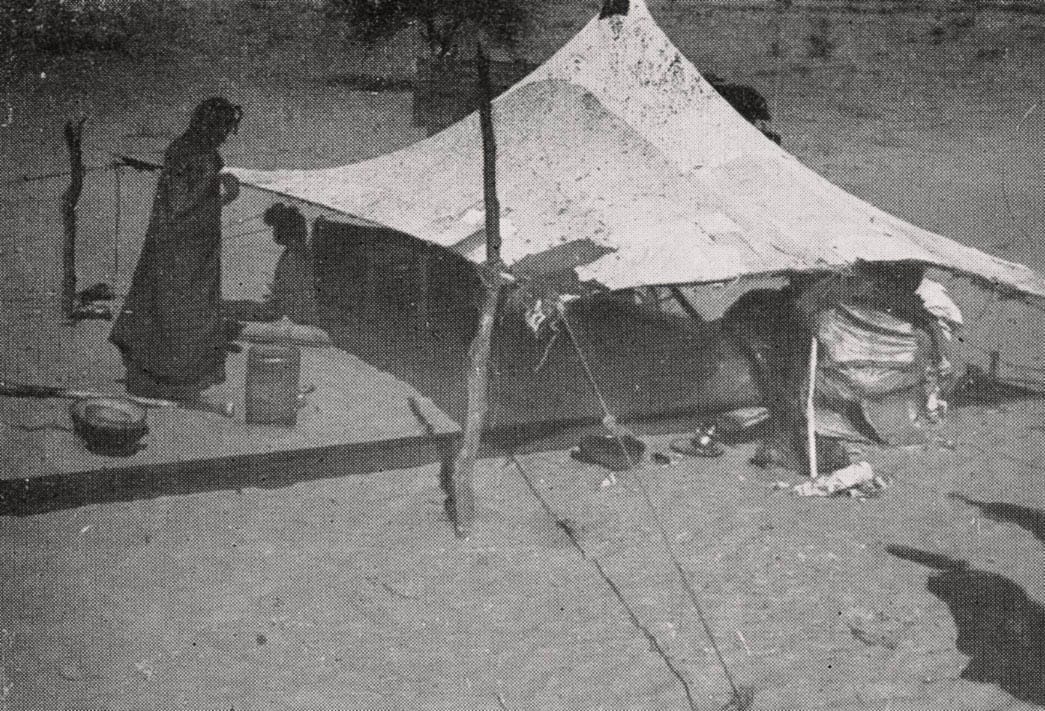

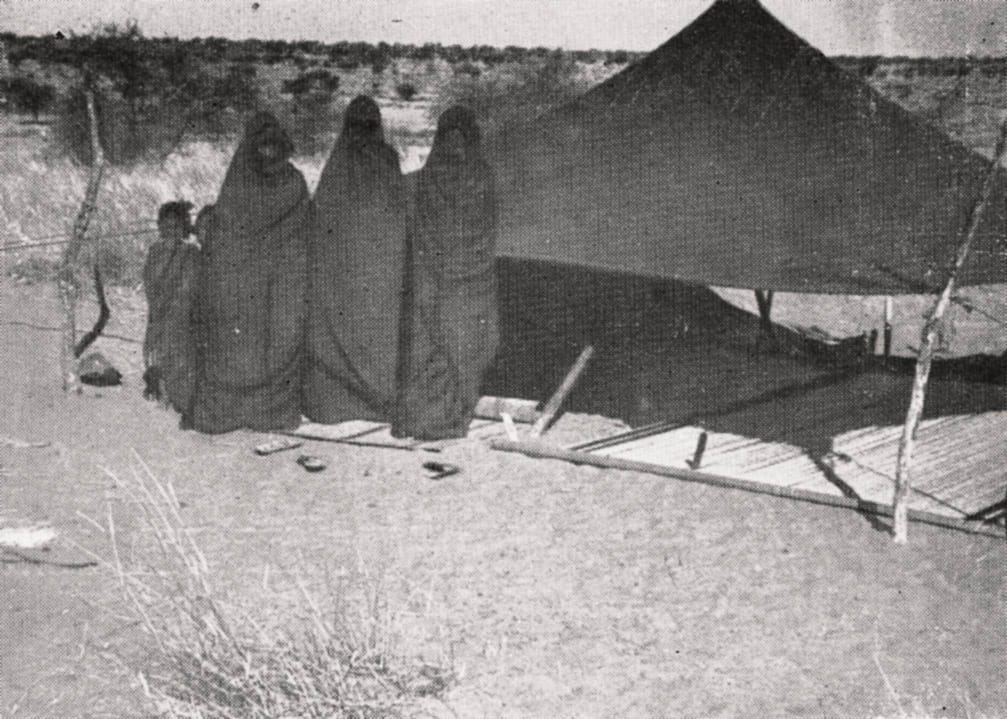

The Moroccan Berber tent, called “aham” (pl. ihamen) in Berber and “hayma” (pl. hiyyam) in Arabic, consists of a velum made of sewn-together fabric strips. This velum is placed on a central beam supported by two poles, while the sides are stretched with ropes and stakes. Poles lift the sides of the tent (fig. 2, 4, 5, 7).

This description includes some additional details:

The woven strips, called “aflij” (pl. iflijen), are about 60 to 75 cm wide, and the number of strips depends on the size of the tent.

The weaving is done on a horizontal loom (4), after which the strips are dyed black.

The weaving materials include wool, goat hair, and plant fibers such as dwarf palm or asphodel.

There are also smaller tents for shepherds and herders, called “aqidum” or “ta’esut” (5).

The large tent, made of more than ten strips, is called “a’assabu,” and those who own it are known as “aït a’assabu.”

In contrast, owners of smaller tents, called “aït uham tuqsift“, are considered of lower status.

__________________

References:

(1) J. Bidaul’t and P. Giraud, L’homme et la tente, 1946.

(2) Mme S. Nouvel, Nomades et Sédentaires au Maroc, 1919.

(3) L. Massignon, Le Maroc dans les premières années du XVIe siècle, 1906.

(4) G. Chantrèaux, Les tissages décorés chez les Beni Mguild, Hesperis, vol. XXXII, 1945.

(5) E. Laot, L’habitation chez les transhumants du Maroc Central, Hespéris, vol. X, 1930, fasc. 2.

__________________

The term *aham* clearly seems to derive from the Arabic word *hayma*.

The velum, perpendicular to the woven bands (*iflijen*), is supported by a woven band that serves as the main tensioner (*adriq uham*), which extends beyond both ends. This band runs over the ridge pole of the tent and is attached to the velum with a decorative stitch of white thread. Each end of this band has a small rod with a cord that stretches the center of the velum, anchored to the ground by a stake. Narrower bands are sewn around the edge of the velum to reinforce it: those on the lower sides (*tirau*, pl. *tiruwin*) and those on the front and rear faces (*tagzi*, pl. *tagziwin*).

In addition to the main tensioner, lateral tensioners secure the velum completely (*tadriqt*, pl. *tidriqin*, or *tafust*, pl. *tifassin*). These woven bands are sewn only along the two lateral edges of the velum. They are stretched with braided cords (*tizment*, pl. *tizmem*) and fastened to the ground with wooden stakes (*azerzu*, pl. *isurza*) (fig. 2, 3, 6, 7, 11) (6).

The main tensioner and lateral tensioners are woven on the same loom as the *iflijen*. However, in the Zemmour region, the use of different colored threads in the warp creates longitudinal patterns in red, black, and orange, sometimes enhanced with knotted points of color and sequins incorporated during weaving.

The tension on the lower sides is maintained by wooden hooks (*ihriben*) sewn to the lateral edges of the tent and pulled tight to the ground with ropes and stakes.

The tent entrance is closed at night with a black veil (*azglef*, pl. *izeglaf*), woven on a vertical loom and sometimes decorated with woven patterns (fig. 11 and 17).

The lower part of the tent, or the sides, is blocked by decorative tent skirts (*tarfaft*, pl. *tirufaf*), long, often highly ornate woven bands made on a high-loom.

_____

(6) Cf. A. Delpy, Note sur le Tissage dans les Zemmour, Cahiers des Arts et Techniques d’Afrique du Nord, n. 3, 1954, pl. III.

_____

In modest tents, they are replaced by mats (*amessu*, pl. *imessa*), woven on a vertical loom without the use of heddles, using a warp of wool mixed with goat hair or dwarf palm fibers and a weft of marsh reeds (*agezmir*). Colored wool threads, forming simple designs, sometimes decorate these mats.

Regarding this lower covering known as *tarfaft*, a story is told among the Zemmour that in the past, when the Beni Amar arrived in the region they now occupy, the Zemmour chiefs gathered one stormy day under a tent to decide whether the newcomers would be fought or accepted into their confederation. One of the chiefs, in favor of their acceptance, used a vivid metaphor: he lifted the tent’s *refafa*—at that moment, wind and rain poured in—and said, “The Beni Amar will be a protection for the Zemmour against our enemies, the Beni Hassen, and just as the *refafa* shields us from the elements, they will defend our left flank.” This argument won over the council, and since then, the Beni Amar have been counted among the tribes of the Zemmour Confederation.

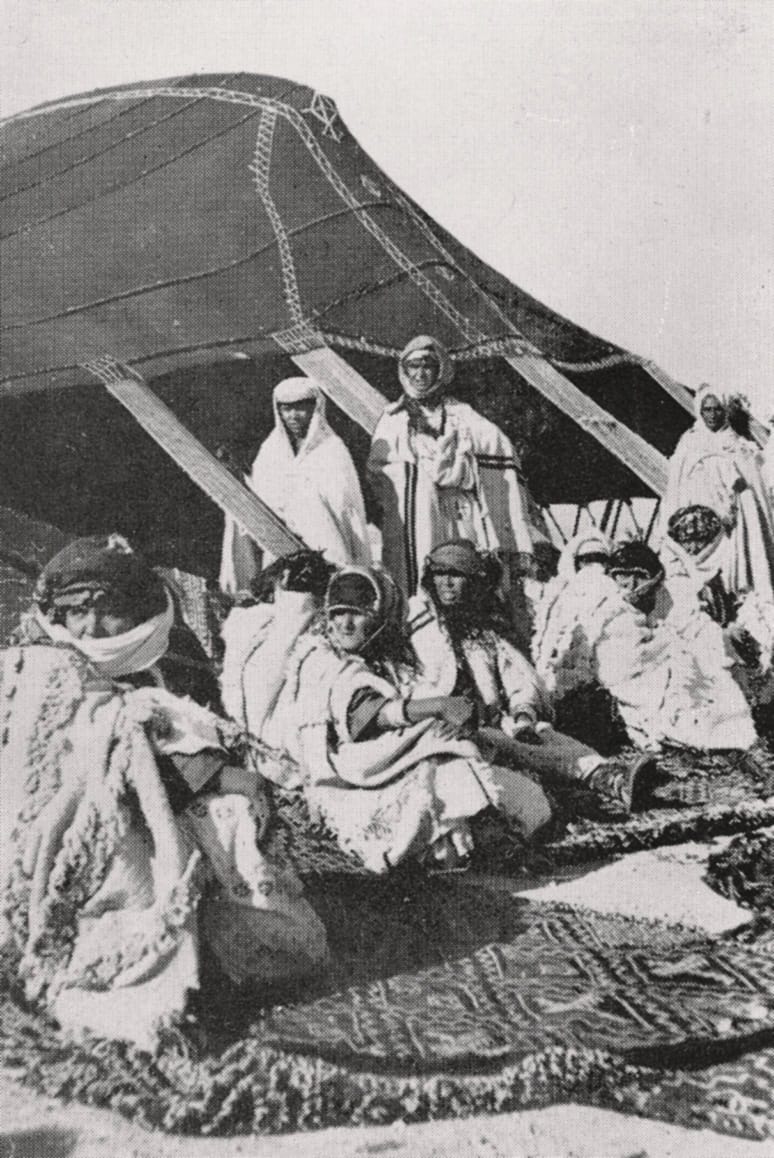

The site where the tent is set up is called *ansa uham*, pl. *ansium* or *ansiwen*, and *adgar* among the southern Berbers (Fig. 2).

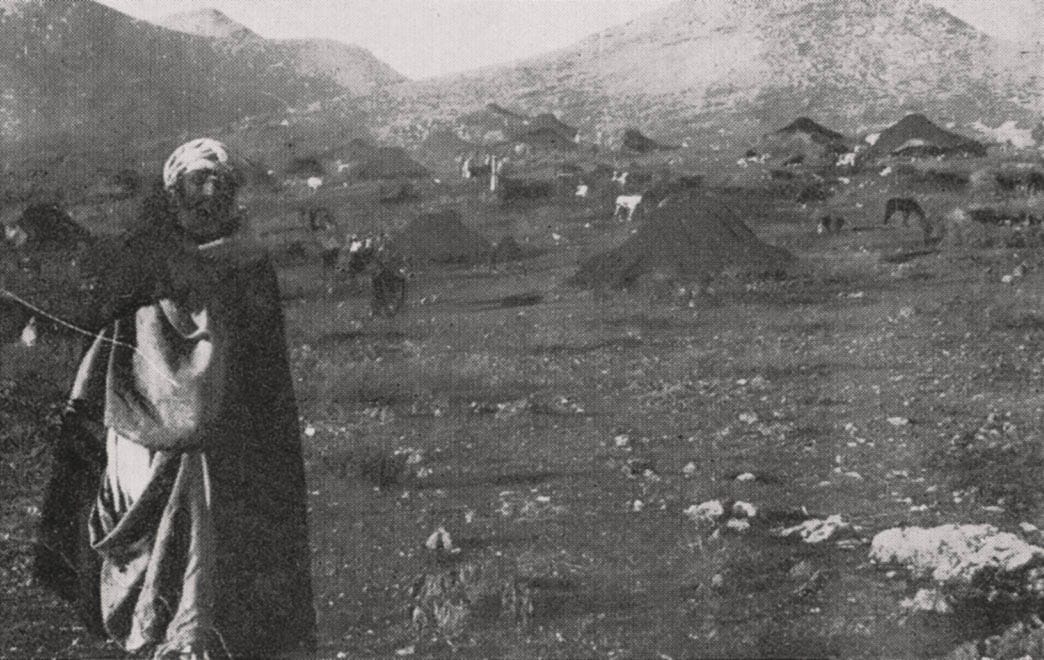

The site of the *douar* formed by several tents is called *amazir*, pl. *imizar* (Fig. 10, 15, 16).

1. Main tensioner: *adriq uhemmar*.

2. Small tensioner: *tadriqt*, pl. *tidriqin*.

3. Tent corner: *tagmert*, pl. *tigemmura*.

4. Lower side hook: *ahrib*, pl. *ihriben*.

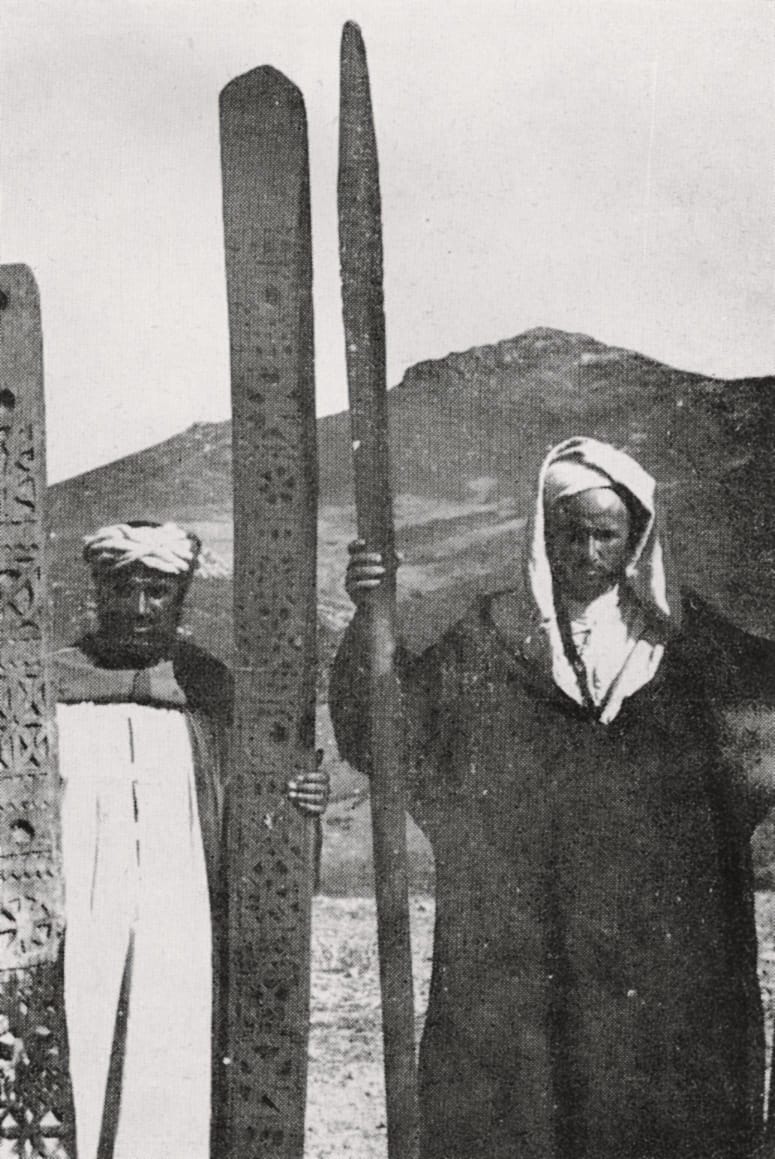

5. Ridge pole: *ahemmar*.

6. Ridge pole upright: *tarselt*, *tirsal*.

7. Stitch under the main tensioner attaching it to the tent’s velum.

8. Protective motif at the tent entrance.

9. Poles to raise the tent flaps.

10. Stakes: *tagust*, *tigusin*.

11. Hammer with one (*azdouz*) or two handles (*tagunt ssin iffassen*).

12. Men’s area: *agella*.

13. Women’s area: *ameddis*.

14. Frame placed between the two uprights of the tent: *tasgaidut*.

15. Pile of rugs, fabrics, and clothes on this frame, forming a separation between the *agella* and *ameddis* (*iqsusen*).

16. Loom: *asetta*.

17. Bench-bed: *tissi*.

18. Rack for sieves: *arun iduda*.

19. Hand mill: *tassirt*.

20. Hearth: *alemsí*, surrounded by various items: lidded dish, water jug, wooden mortar, funnel, wooden bucket.

21. Grain and wool storage in bags.

22. Guest reception area with mat (*agertil*) and cushions (*tisuna*), all covered by a mat (*amessu*).

23. Tent skirt: *tarfaft*, pl. *tirufaf*.

24. Area reserved for young goats and lambs.

25. Type of ridge pole of a Moorish tent.

—

The frame supporting the velum consists of a ridge pole (*ahemar*) held up by two wooden uprights called *tarselt* (pl. *tirsal*).

The *ahemmar* is often decorated with simple geometric carvings such as circles, teeth, chevrons, diamonds, crosses, etc. (fig. 7, 13, 14).

In a tent made up of five *flij* (panels), the three central *flij* rest on the ridge pole, while the other two are supported by the *adriq*. These outer panels (*tamadla*), which are wider than the others, are woven on a vertical loom.

Sewing the *flij* is always a man’s job. The tent’s edges, which tend to sag, are lifted with poles (*a’amud*, pl. *i’amuden*). A small trench (*agemmun*) is dug around the tent to prevent rainwater from entering (fig. 7).

E. Laoust suggests that the use of tents by the Senhaja likely originated from the Bedouins through the Zenetes, who were once great nomads.

INTERIOR DESCRIPTION OF THE TENT

The pillars (*tirsal*, singular *tarselt*) divide the tent into two sections. The space between these sections is blocked by a pile of bedding and clothes (*iqsusen*) stored in a net (*tasgaidut*).

The women gather in the part of the tent where the hearth is located (fig. 5).

The other part (*agella*) is reserved for men and guests (fig. 4).

In the women’s area, you find cooking utensils, an earthen bench covered with dwarf palm leaves and topped with a mat or carpet serving as a bed (*tissi*), the vertical loom (*asetta*), and, in one corner of the tent, the hearth (*almessi*). In the opposite corner are the hand mill (*tissirt*) and the sieve storage net (*aru n iduda*) (fig. 7).

In the *agella*, supplies of wool, maize, barley, sacks, and saddles are stored. Toward the center, the men and guests settle down for the night, using a ground mat (*amessu*) to protect themselves from the cold. It is also in a corner of the *agella* where weak lambs and goat kids, too frail to follow their mothers to pasture, are kept.

These arrangements, noted by E. Laoust among the Zemmour, are found with slight variations among all the nomads of the Middle Atlas.

The tent is always guarded by dogs, sometimes tied to a chain.

In the past, Léon the African noted that when a tent owner was absent, they would leave a spear stuck in the ground in front of the tent, “thus warning that entry to the tent is forbidden in their absence.”

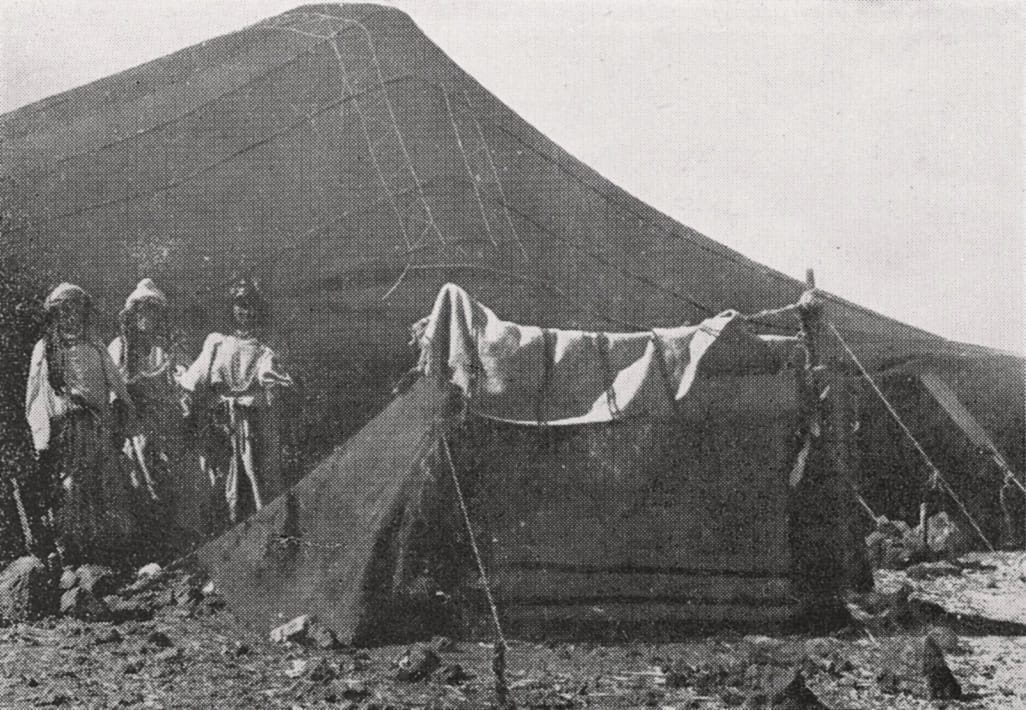

Tents are usually arranged in a circle (*douar* in Arabic; in Berber, *asun* or *tigemmi*), with the outer side blocked by the *azeglef*, while the other side faces the center of the circle (fig. 15 and 16).

When the head of the tent migrates, the dismantling and reassembling of the tent is done by the women. The various parts of the tent, along with all the furniture, are carried by pack animals such as horses, mules, donkeys, camels, and oxen.

To set up the tent, after choosing its location following certain customs, the velum with its straps and hooks is spread out. The ropes are attached to stakes, which are driven into the ground using a single or double-handled mallet (*azduz*, *tadgunt ssin ifassen*) (fig. 7 and 11). First, the stakes attached to the main strap are hammered in, followed by the stakes at the corners (*tigmert*, pl. *tigemmura*). Then two or three women slip under the velum and raise the ridge pole (*ahemmar*) using the two upright posts (*tirsal*). Once the tent is standing, the ropes for the lateral straps and the hooks (*ihriben*) on the lower sides are secured with stakes to stabilize the structure.

The side panels, known as *izeglaf*, are then pinned up. When setting up a douar (encampment), this operation must be done simultaneously by the owners of the tents facing each other.

Care must be taken when setting up the tent to ensure that one of its corners is not directed toward a neighbor’s entrance. This is considered a bad omen for the neighbor, and if it happens, it is better to take down and reposition the tent. The term for setting up a tent in Berber is *bnu*; to live in a tent is called *zeddeg*.

A *flij* (tent panel) typically lasts no more than five years. Worn-out *flij* (*ahdum*) are repurposed into sacks or small shepherd tents.

The sewing of tent panels (*iflijen*) and the replacement of old *flij* with new ones are always done by men. These craftsmen, called *imegnan*, use large needles (*tisegnit*) and thick, undyed wool threads. The women of the tent serve breakfast (*lefdor*) to the men, who have prepared the replacement panels in advance. Afterward, the craftsmen sew the new panels, and when the work is complete, a couscous meal (*afettal*) is served.

Above the tent’s entrance, between the two lines of stitching where the *adriq* meets the velum, a decorative motif is added, which can vary: a diamond, cross, or horse. Among the Beni Mtir, this is called *timratin uham* (“mirrors of the tent”) or *ayur* (“the moon”), with a protective purpose.

Various amulets protect the tent, its occupants, and the livestock it shelters.

Several rituals accompany these works, including the transportation of the repaired tent to its new location, which must not be the same as the previous one. In the evening, a sheep or goat is slaughtered, or in their absence, a few chickens, and a dinner is held with the participation of the *imegnan* and neighbors who helped. They then offer their good wishes to the tent owner.

The tents in central and western Morocco show little variation, but those in the high regions of the Beni Mguild and Zaïane tribes are highly angular, and the straps are black, as is also seen in the Gharb and Chaouia regions (fig. 9, 11, 12, 17).

In eastern Morocco, the tent resembles the type used by Bedouins in Algeria, with the straps often decorated with more varied geometric patterns than in the Zemmour, achieved by changing the colors of the warp threads. In the upper Moulouya, the tent of the Oulad Khaoua tribe is equipped with only a narrow beam as a ridge pole.

In Mauritania (fig. 18 and 19), the central uprights that hold the ridge beam cross, and the *iflijen* are often replaced with white cotton fabric. However, the lower panels are made of painted and cut leather, as is the case with the Tuaregs.

A small tent is called *tahamt*. The same word refers to a small person: “*am tagust tehamt n tejalt ihedamen uwudjil*”—as small as the peg of the widow’s small tent, who has to work to feed her orphans.

The poverty of widows forces them to live outside the douar in a small, reduced-sized tent.

Despite advancements in agriculture, the tent is still highly valued in Morocco. Nomads are very fond of it and, in the summer, often prefer it to the *taddart* (house) (7).

Nine centuries ago, the Almoravid leader, Abdallah ben Yassine, lived in a tent while the city of Marrakech was being built.

In high-altitude regions, not everyone migrates during winter, and it is common to see a tent covered in snow sheltering its inhabitants, despite temperatures often falling below zero.

In conclusion, it is highly likely that in certain impoverished regions suitable only for livestock farming, the tent will persist indefinitely as a form of housing.

A. DELPY.

—

(7) I remember visiting Caïd Amahroq of the Zayane at his estate “Jenane Imes” near Khénifra; although he had a large masonry house, he preferred living in a tent next to it.